John Stevenson can relate to the thousands of people who flock to the Peavine Trail each year to take in the views of Granite Dells.

In a different time, Stevenson also spent plenty of time walking and riding through the scenic corridor. Only, for him, the trips were not recreational and they occurred either on a train or alongside one.

Even though the Peavine route was a regular one for Stevenson in his many rears as a railroad brakeman on the route, he said the views were not lost on the crew.

Even though the Peavine route was a regular one for Stevenson in his many rears as a railroad brakeman on the route, he said the views were not lost on the crew.

“It was beautiful – especially when you got into the Granite Dells Area,” Stevenson said who is now a retired railroad worker living in Clarkdale. We sometimes had to get out and walk it. “I remember walking alongside the train, looking at the views.”

Stevenson, who retired in 1998 after working for the Atchinson Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad for 44 years, began his career in 1954, when Prescott was still the major base for the line.

Following, are some short stories by John Stevenson.

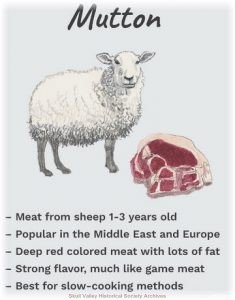

THE MUTTON REBELLION

“No operation or safety rules violated.”

As the youngest promoted conductor in seniority and in fact I was not yet 23, I could be assigned to any job, like it or not, if no others wanted it. After construction of the roadbed with massive cuts, fills, grades and curves, the work train to which I was assigned as conductor began to lay 1700-foot sections of prefabricated track panels.

This was an amazing innovation developed by the Santa Fe four years earlier for the Williams-Seligman line change and now utilized by all U.S. and Canadian railroads. The panels were dragged off rollers on special built flat cars by a peculiar machine called a straddle buggy. Following my train was a ballast train.

Together we could lay over two miles of rail per/train load. The panels were then welded together into a solid ribbon of steel rail thus eliminating the · familiar clackety-clack.

The final touch of this operation were Navajo trackmen with jackhammers, spike mauls and tamping machines. Together we went from bare ground to heavy high-speed trackage in one continuous motion. “John Henry, the spike driving man” would have met his match with these Navajo braves.

The final touch of this operation were Navajo trackmen with jackhammers, spike mauls and tamping machines. Together we went from bare ground to heavy high-speed trackage in one continuous motion. “John Henry, the spike driving man” would have met his match with these Navajo braves.

In the 1880′ s as the Atlantic Pacific/Santa Fe progressed westward across Indian lands; one of the conditions was – employment of these Native Americans as track maintenance. This became a win-win agreement for all concerned. The term “gandy dancer”, slang for track people, was not used on the Santa Fe. In addition to Navajo’s; Laguna’s, Acoma’s, Zuni’s and Hopi’s were employed. Many made rewarding careers as maintenance-of-way employees. Some became foremen, track supervisors, road masters .and in later years conductors and locomotive engineers.

At the time of the Prescott bypass from Skull Valley across Chino to Drake in the early 60’s, the majority of these tribesmen were part-time experienced trackmen living on the reservation and would report for construction gangs as needed. Four ten-hour workdays allowed them to go back to the reservation on Thursday and return on Monday.

Transportation was provided by the railroad. Also, commissary and bunk cars provided workday requirements. Things went smoothly for a few weeks until the mutton rebellion. The natives became restless and just short of hostilities, refused to work.  Their spokesman and Medicine Man, Hosteen Yellowhair, advised that the braves were tired of white man grub and demanded mutton or we go home. The Pueblo types were somewhat amused by their Navajo counterparts and probably didn’t like sheep in any form.

Their spokesman and Medicine Man, Hosteen Yellowhair, advised that the braves were tired of white man grub and demanded mutton or we go home. The Pueblo types were somewhat amused by their Navajo counterparts and probably didn’t like sheep in any form.

Nevertheless, mutton was quickly brought in from somewhere. The cooks quit and were replaced by natives and we went back to work, finishing the line. Officials drove the golden spike at Skull Valley commemorating the occasion; their pictures were in the paper. The Indians and me were treated to Strawberry Soda and doughnuts. I had indigestion for a week.

By: John Stevenson